Kanemitsu (兼光), Kenmu (建武, 1334-1338), Bizen, first name „Saemon no Jō“ (左衛門尉), son of Osafune Kagemitsu (景光), that means he was the 4th gen. Osafune mainline, it is said that he was one of the Masamune no Jittetsu, since oldest times there is the theory that there were two generations Kanemitsu active. San ́indō (山陰道), saijō-saku.

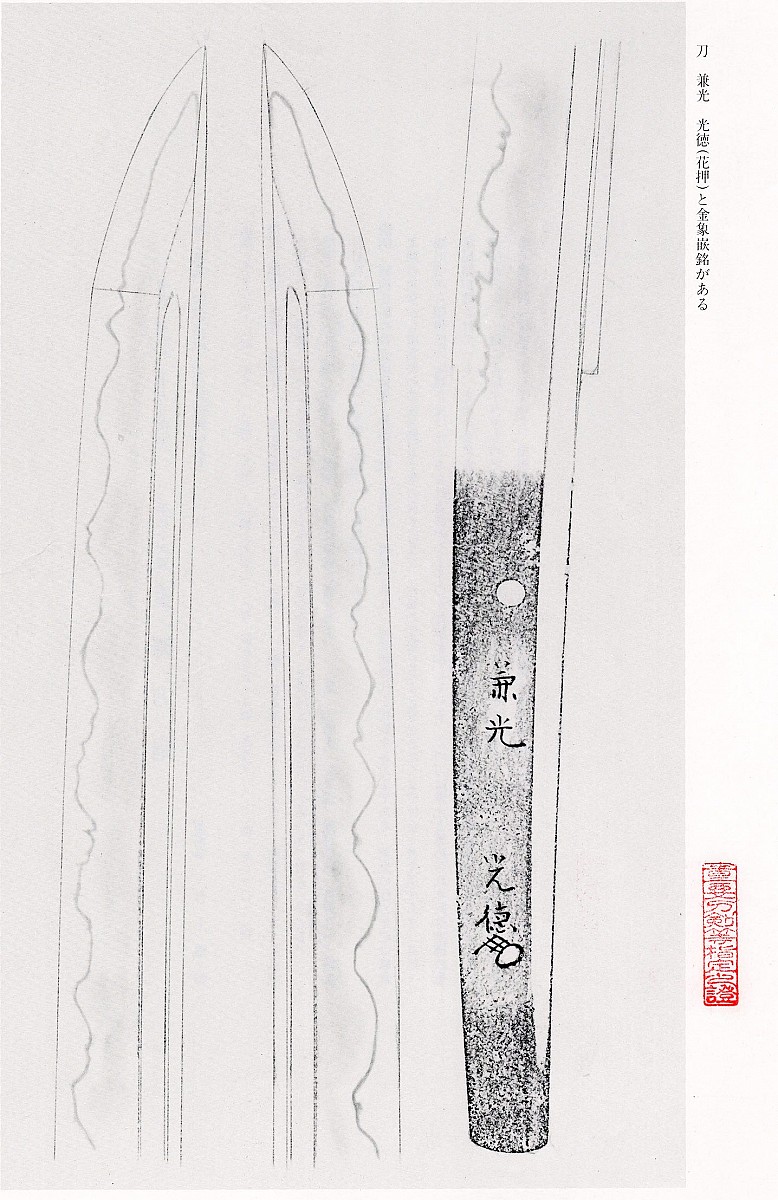

Jūyō Tōken Kanemitsu Katana: nagasa: 69.6 сm; sori: 1.5 сm; motohaba: 3.0 сm; sakihaba: 2.1 cm; kissaki nagasa: 5.8 cm; nakago nagasa: 18.3 сm; nakago sori: 0.2 сm. This sword bear a kinzōgan-mei by Hon’ami Kōtoku; the authenticity of kinzōgan-mei was confirmed by the NBTHK in 1990 and by Tanobe Michihiro in 2009; the sword was shortened and delicately re-sharpened by Hon’ami Kōetsu at the very beginning of the 1600s; the double habaki for the sword was made of solid gold; the sword was the family heirloom of the Shimazu clan (島津); was polished by Fujishiro Matsuo (藤代松雄, Ningen Kokuhō, 1914–2004); the sword was in the collections of Murakami Shintarō (村上慎太郎) and Murakami Kensuke (村上建輔, Fukuoka Prefecture). The sword is presented together with a koshirae made for the sword in modern times.

Designated as Jūyō Tōken at the 36th jūyō-shinsa held on the 25th of May 1990.

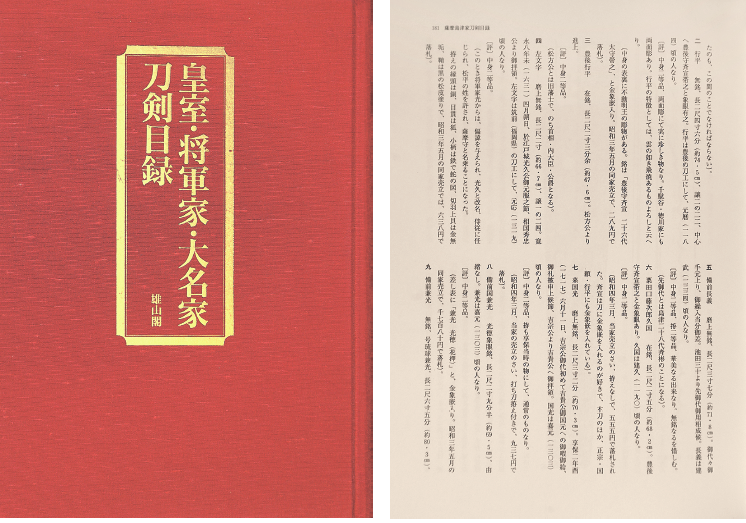

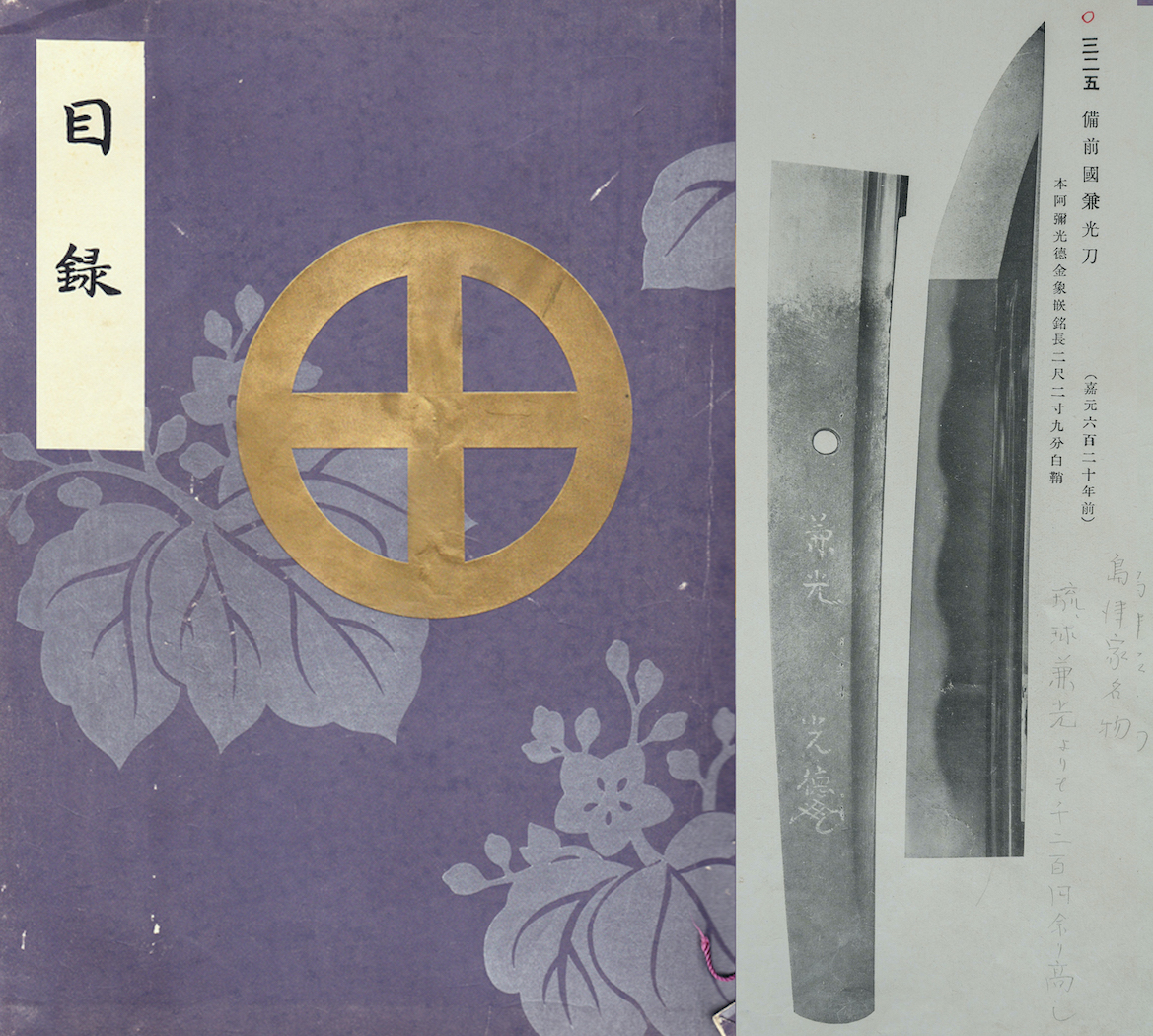

Publications: NBTHK Jūyō Tōken Nado Zufu, Volume 36; Shimazu Clan Family Heirloom Catalogue, 1928, No. 325; the sword was sold at an auction of the family heirlooms of the Shimazu clan on May 18, 1928, for 1,780 yen; the buyer’s name was Kitaoka (北岡); Kōshitsu, Shōgun-Ke, Daimyō-Ke Tōken Mokuroku, 1997, No. 8, p. 181.

Figure 1: Kōshitsu, Shōgun-Ke, Daimyō-Ke Tōken Mokuroku.

Currently, there are many extant works by Bizen Kanemitsu, both signed and unsigned, so Kanemitsu’s swords are not that rare. Despite all of this diversity, it is difficult to encounter another work with the outstanding quality and high degree of preservation that this sword has. The value of this sword is not determined by the rarity of the work or by its well-known master. Although Kanemitsu is certainly one of the most revered smiths, the value of the sword presented here is determined by four factors: its origin, the presence of Kōtoku’s kinzōgan-mei, its shortening having been done by Hon’ami Kōetsu, and its excellent degree of preservation.

Figure 2: Shimazu Tadashige (1886-1968).

This sword by Kanemitsu was sold by the Shimazu family, which was one of the three most powerful clans in Japanese history, and can thus be regarded as the legacy of this clan. The provenance of a sword is often hard to prove on the basis of documents. In this case, the provenance is confirmed by clan records (namely, the Kōshaku Shimazu Ke Zōhin Nyūsatsu Mokuroku catalogue (published in 1928 in Tōkyō) and NBTHK documents, indicating that this sword belonged to the Shimazu clan. The Figure 13.3 shows the corresponding page from the Shimazu clan’s catalogue. The catalogue itself, which is among the documents accompanying the sword, is almost the only printed source available that makes it possible for us to understand the objects that constituted the family legacy of a very powerful and influential Japanese clan. This catalogue can still be found and purchased from traders of rare books in Japan, although it is indeed quite rare to find. Even more impossible would be trying to, step-by-step, follow the history of ownership for any sword presented in the auction catalogue, if it didn’t have a set of documents verifying its history, as this Kanemitsu sword has.

Figure 3: Shimazu Clan Family Heirloom Catalogue.

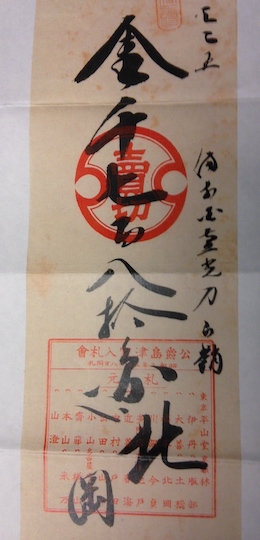

For example, among the papers accompanying this Kanemitsu, the original label was preserved (Figure 13.4), indicating the price at which this sword was bought (1,780 yen), together with the name of the buyer (Kitaoka). This document clearly indicates that this is one of the highest prices paid for any of the swords during this auction. For comparison, the following data can be cited: The “Ryūkyū Kanemitsu” (琉球兼光), the famous meitō described above, was sold for 618 yen; and the “Tsuruga Masamune” (敦賀正宗), formerly owned by Otani Yoshitsugu (大谷吉継)—a close friend of Ishida Mitsunari and a vassal of Toyotomi Hideyoshi—was sold for 3,600 yen.

Figure 4: Original tag with the name of the buyer (Kitaoka from Kyōto).

Some documents that accompany a sword (including important historical ones) are very often held by dealers and then lost, because they were no longer important, significant, or relevant to the process of selling the sword. Such a thing happens because many dealers trade a great number of items: they simply do not have time to correctly analyze the set of documents that accompanies every sword they own. Many important papers are lost during this process, because after the sale of the sword it is difficult to understand which item is mentioned in the document accidentally retained by the dealer. This system of selling swords has been in place for centuries, and it clearly did not contribute to preserving all information about the provenance of an item. That is why great respect should be paid to experts and collectors who retain each, albeit insignificant, document, so that we can reconstruct certain historical events related to each sword.

The next important attribute of this word by Kanemitsu is its evaluation, made via a kinzōgan-mei by Hon’ami Kōtoku (本阿弥光徳). This representative of the Hon’ami main line, as its 9th generation, was a legendary person in the family’s history and in the history of Japanese swords as a whole. In the NBTHK papers that accompany the sword (Jūyō setsumei), it is noted that Kōtoku’s kinzōgan-mei, presented on the nakago of this sword, was made with slightly smaller kanji than usual, and so the to mei ga aru (と銘がある) comment was added. This does not mean that the mei is not authentic (see below). Incidentally, the term translates literally as “bears the inscription . . .”

In practice, this NBTHK comment usually has two ways it can be used. The first case: Experts are in

agreement that the signature needs additional study and research. In this case, its authenticity is questionable, because it is accepted that all the research that could have been done with respect to the master’s signature has long ago been conducted, and the probability of finding any new information that would back the uncommon signature in question is low.

The second case: Experts are in agreement that although non-standard, the signature falls within a variation of a master’s signature during his period of creativity and that it is acceptable to treat it as authentic under these parameters.

The kinzōgan-mei of this sword by Kanemitsu is confirmed. Thus, we have here the second case of applying the “to mei ga aru” comment. A “to mei ga aru” entry always needs a detailed analysis of the evaluation documents. Detailed research is required for each specific case, because this can be an important factor in the attribution of both swords and koshirae elements, as well as other art objects.

Furthermore, the NBTHK comments that Kōtoku’s kinzōgan-mei on swords is an extreme rarity. Indeed, this phenomenon can be found only in isolated cases. Among all the masters and all the extant swords, when this happens, it is literally like hitting the lottery. In addition to this sword by Kanemitsu, the following works have Kōtoku’s kinzōgan-mei: Jūyō Nos. 5, 9, and 11; Tokubetsu Jūyō No. 18; Jūyō Bijutsuhin Nos. 671, 797, and 837; and Jūyō Bunkazai Nos. 273, 412, 471, and 689. We should particularly note six swords with Kokuhō status, also having Kōtoku’s kinzōgan-mei: “Heshikiri Hasebe,” “Izumi Masamune,” “Nakatsukasa Masamune,” “Inaba Gō,” “Ikoma Mitsutada,” and another Mitsutada with a nagasa of 72.5 cm. In total, only 17 swords that are extant have Kōtoku’s kinzōgan-mei. We can see that only 4 of them have Jūyō and Tokubetsu Jūyō status, while the others have a higher one. Most swords with Kōtoku’s kinzōgan-mei are of Kokuhō status.

For comparison, the following statistics can be cited. In total, there are 497 kinzōgan-mei that one or another expert made on swords, and 144 were made on parts of the koshirae. Such statistics show the rarity of the kinzōgan-mei itself, especially when performed by Hon’ami Kōtoku. Considering the number of swords that have it, we can conclude that it is an utmost rarity to encounter Kōtoku’s kinzōgan-mei. In order to see such a rare art object, one should plan on visiting a Japanese museum.

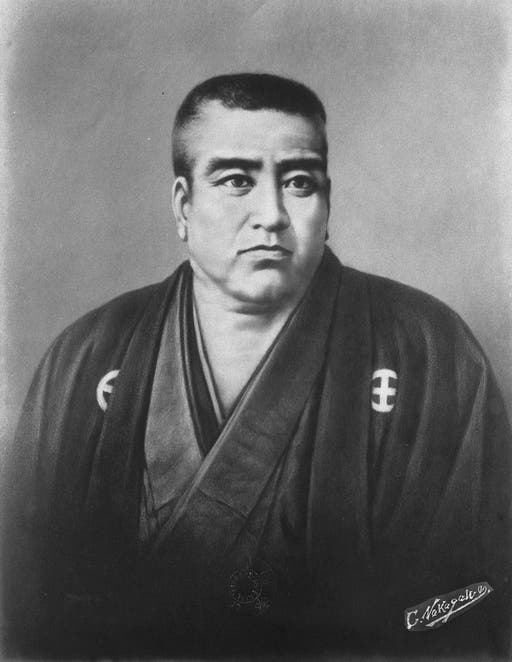

This Bizen Osafune Kanemitsu sword was a family treasure of the Shimazu clan for many generations. This sword, with Hon’ami’s Kōtoku attribution, had a prominent position in the clan’s collection and was closely connected with its history. In view of this, we can assume that it was examined by prominent historical figures, including Saigō Takamori, who at one time was a samurai for the clan.

Figure 5. Saigō Takamori (西郷隆盛, 1828–1877).

(excerpt from Chapter 13, pp. 312-329, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces )

Original content Copyright © 2019 Dmitry Pechalov